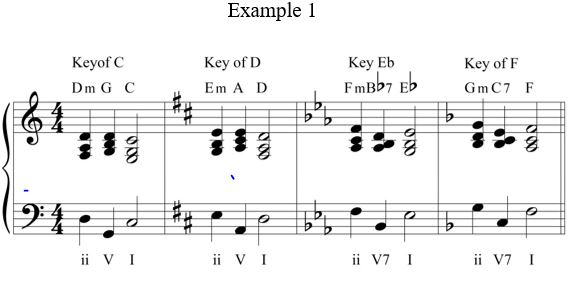

One day as I was conducting a workshop on the topic, “Playing by Ear” someone commented, “You use chords as if they’re a language for you.” I took that as a compliment, and I’ve pondered the implications of her words. My understanding of language began in elementary school where we learned about nouns, pronouns, verbs, and more. Diagramming sentences helped us see the structure of a sentence. Through the study of Latin and German I became even more aware of the structure of a sentence. There are chords that are like verbs; they create movement. Through the study of music theory I began to see how chords interact. Much can be learned by listening and observing their behavior. A good example of chords in action is the progression ii V I often heard at final cadences.

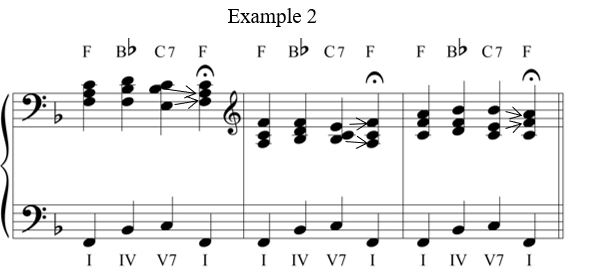

As I’ve said a number of times in my tutorial, “We need to organize the sounds that have been floating around in our ears, fingers, and voices since the day we started making music.” Learning to hear and use the basic chords [I, IV, and V(7)] is an important first step in understanding chords. They can be played as a common tone progressions, beginning with different positions of the tonic [I] chord:

Perhaps you’ve noticed how the 7th of the C7 chords [Bb] is resolved downward to the 3rd of the F chord [A]. A strong sense of movement results as the 3rd of the C7 chord rises to F, the root of the tonic chord [I]. To develop a greater awareness of the strong tendency of these pitches, play and resolve these two pitches in each of the different positions shown in the above example (see arrows).

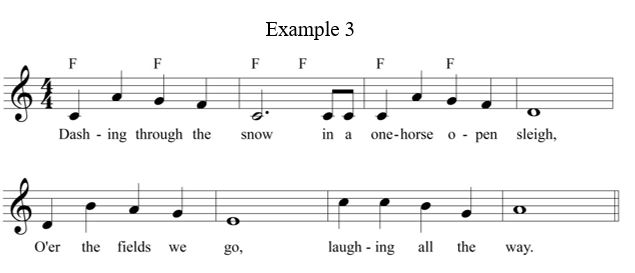

There are many songs that can be accompanied with these basic chords. Let your ear guide you in selecting the right chords. Let’s apply the basic chords in accompanying “Jingle Bells.” Repeat the F chord as you sing, “Dashing through the snow….” Change to a different chord when your ear begins to hurt because of a clash between the melody and the F chord. In the following example you see where the F chord no longer fits. The pitch, D, is part of the IV chord [Bb]. The Bb chord works well until the pitch E on the word, “go” which is part of the C7 chord.

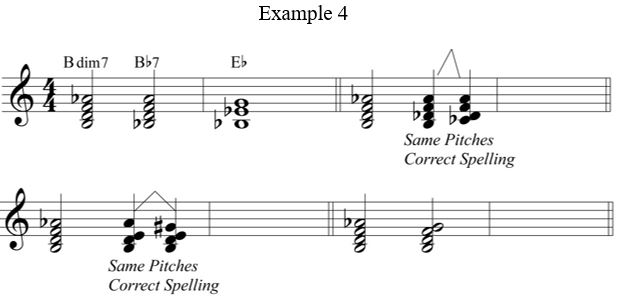

The following exercise will increase your skill in resolving dominant seventh chords. The distance between the pitches of a diminished 7th chord is a minor 3rd which is a span of three half steps [minor 2nds]. When you lower any one of the pitches, that pitch becomes the root of a dominant 7th chord. In the first music example below, the root of the diminished 7th chord is lowered, and the result is a Bb7 chord which is resolved to Eb. Resolve each of the dominant chords formed by lowering a pitch of the diminished 7th chord (see Example 4).

Note: There’s a video presentation of this under Teaching Tips (see “An Adventure in Creating and Resolving Dominant 7th Chords”).

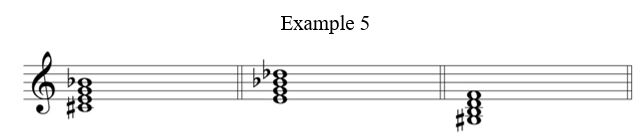

For more experience in altering diminished seventh chords to form dominant seventh chord, Start with each chord in the following example. Lower the root, then the 3rd, 5th, and 7th.

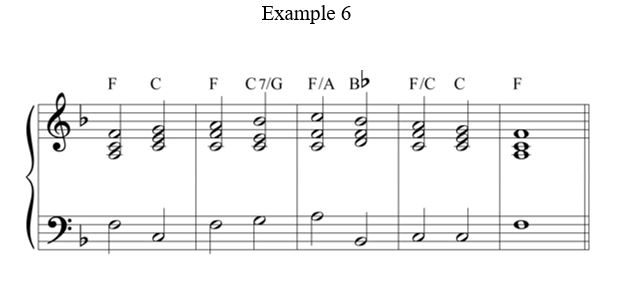

The basic chords can also be used with a scale as in Example 6.

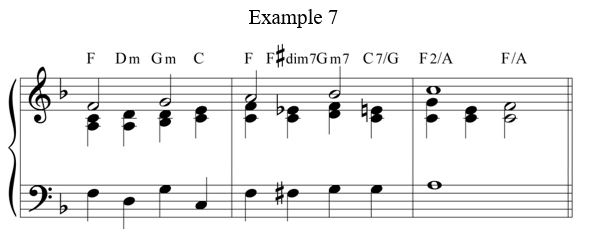

Additional enrichment is possible by adding minor chords and diminished chords as in Example 7..

In the above example, there is strength in the chord progression: Dm Gm C F. This is called “Succession by 5ths.” The bass moves up a 4th (D to G), down a 5th (G to C), and up a 4th (C to F). The F#dim7 leads strongly to Gm7. Much can be learned by thinking about the behavior of the chords we’re playing. I appreciate the comment of my friend, Becky, who said, “You use chords as if they’re a language.” Gaining a new perspective is an important part of the creative work of an artist. A perspective that I offer as encouragement is this: “Improvisation enables us to express a part of ourselves that might never find expression if we limit ourselves to playing only what others have written.”

Comments are closed.